Building Bridges and Honoring Tradition Through Leadership: A Leadership Framework for the non-Native School Leader Serving in Predominately Native Schools

Leadership Framework for The Non-Native School Leader.

This article introduces the Leadership Framework for the Non-Native School Leader. This framework is designed to support non-Native school leaders serving in predominantly Native schools in meeting the unique challenges in their leadership roles.

In the dynamic landscape of education, the role of a school leader extends far beyond administrative duties. In schools with predominantly Native student populations, the responsibility to preserve cultural heritage and empower Indigenous communities falls heavily on the shoulders of non-Native school leaders. To navigate this complex terrain effectively, a robust leadership framework is essential. The Non-Native School Leader Leadership Framework stands as a beacon of guidance, comprising five integral pillars that uphold the values of:

1. Native Educational Sovereignty,

2. Decolonization of leadership practices

3. Culturally affirming practices

4. Prioritization of Indigenous knowledge

5. Collaboration

It’s not uncommon for a school leader entering a new assignment in predominantly Native spaces to come with a backpack full of great ideas. Often, however, those ideas are met with suspension from Native communities for various reasons. Most often, it is because many of the ideas new non-Native school leaders bring utilize practices steeped in colonization and assimilationist ideology. This happens frequently in ways that may not be clearly or easily discernable to the school leader.

Another challenge facing non-Native school leaders serving in predominantly Native schools is the disconnect between the perceived role of the school leader versus the actual role of the non-Native school leader serving in Native communities. The non-Native school leader's perceived role is to improve students' academic outcomes, improve graduation rates, address issues related to chronic absenteeism, and prepare students for life after high school. The actual role of the school leader is to build capacity in the community so that leadership can rest within the community. They are building leadership capacity in Native teachers and Paraprofessionals, teaching students how to lead, and providing opportunities for them to lead.

The Leadership Framework for the non-Native school leader can provide solid guidance and strategies to address this disconnect, helping the school leader realign practices and priorities to support Native Educational Sovereignty. Utilizing the Leadership Framework for the non-Native School Leader, leaders can be crucial in supporting educational excellence while honoring and preserving Native cultures. Success in this context requires ongoing reflection, adaptation, and a genuine commitment to serving the unique needs of Native students and communities.

Leadership Framework for the non-Native School Leader

A model of the Leadership Framework for the non-Native School Leader. Created by: Dr. Ralph M. Watkins. July 24th, 2009

Reviewing the Five Pillars

Pillar # 1. Native Educational Sovereignty

At the core of this leadership framework lies the principle of Native Educational Sovereignty. The concept of Native Educational Sovereignty stands as a beacon of hope and empowerment for Indigenous communities striving to reclaim control over their educational systems. Rooted in the principles of self-determination and cultural autonomy, Native Educational Sovereignty represents a fundamental shift in the education paradigm for Native peoples. For the non-Native school leader, embracing Native Educational Sovereignty is not merely a symbolic gesture but a tangible commitment to justice, equity, and the empowerment of Indigenous communities in reclaiming control over their educational destinies.

The Educational Sovereignty pillar emphasizes empowering Native communities to exercise self-determination in shaping their educational systems. Non-Native school leaders must respect and support initiatives such as Native-controlled schools, language revitalization programs, and culturally appropriate teaching methods. By recognizing and upholding the sovereignty of Native communities, school leaders can foster an environment that celebrates and preserves Indigenous traditions.

It would be difficult to understand why Educational Sovereignty is such an important pillar in supporting the leadership of the non-Native school leader without recognizing the profound impact of colonization on the learning experiences of Native individuals, mainly through the establishment of boarding schools and the decentering of Indigenous knowledge. Furthermore, it explores the critical role of non-Native school leaders in embracing Native Educational Sovereignty and fostering a learning environment that honors and uplifts Indigenous communities.

Impact of Colonization on Native Learning Paradigm

The legacy of colonization has cast a long shadow over the educational experiences of Native peoples, fundamentally altering their cultural identities and eroding traditional knowledge systems. One of the most harrowing manifestations of this legacy was the establishment of boarding schools, where Native children were forcibly removed from their families and communities to undergo assimilation into Eurocentric norms. These schools aimed to strip Indigenous youth of their languages, cultures, and identities, instilling shame and erasure of their heritage.

The trauma inflicted by the boarding school system reverberates through generations, leaving deep scars on Indigenous communities. The devaluation of Indigenous knowledge and the imposition of Western educational frameworks marginalized traditional ways of learning and knowing. As a result, many Native students found themselves caught between two worlds, struggling to reconcile their cultural identities with the educational systems that sought to erase them.

Decentering of Indigenous Knowledge

Central to the colonial project was decentering Indigenous knowledge within educational settings. Traditional ways of learning, rooted in community-based practices, storytelling, and intergenerational wisdom, were dismissed as inferior to Western academic disciplines. Indigenous languages were suppressed, cultural practices were prohibited, and the epistemologies of Native peoples were invalidated. By relegating Indigenous knowledge to the margins, colonial education systems perpetuated a cycle of cultural erasure and disempowerment.

Native students were denied the opportunity to learn from their elders, engage with their ancestral teachings, and cultivate a deep connection to their cultural heritage. The consequences of this decentering reverberate in the present day, contributing to disparities in educational outcomes, cultural alienation, and a loss of intergenerational knowledge transfer.

Embracing Native Educational Sovereignty as a Non-Native School Leader As non-Native school leaders step into roles within predominantly Native-enrolled schools, embracing Native Educational Sovereignty emerges as a vital imperative. By recognizing the inherent right of Indigenous communities to govern their educational systems, non-Native leaders can actively support revitalizing Indigenous knowledge, languages, and cultural practices within the school environment. Embracing Native Educational Sovereignty entails relinquishing control and centering the voices and perspectives of Native stakeholders in decision-making processes.

Non-Native school leaders must collaborate meaningfully with Indigenous community members, prioritize Indigenous knowledge in curriculum development, and create space for culturally affirming practices to thrive. By actively working to dismantle colonial legacies within educational institutions, non-Native school leaders can pave the way for a more equitable, inclusive, and culturally responsive learning environment.

By understanding colonization's impacts on Native individuals' learning paradigm, acknowledging the decentering of Indigenous knowledge, and actively embracing Native Educational Sovereignty as non-Native school leaders, we can collectively work towards a future where Indigenous students thrive academically, culturally, and spiritually. It is through the recognition and celebration of Native Educational Sovereignty that we can pave the way for a more just and equitable educational landscape for all.

Pillar # 2 Decolonization of Leadership Practices

The final pillar of the framework calls for the decolonization of leadership practices. Non-Native school leaders must critically examine and challenge colonial legacies embedded within educational systems. School leaders can create an environment that promotes equity, justice, and cultural revitalization by dismantling oppressive structures and embracing culturally responsive leadership practices. Decolonization of leadership practices is essential to fostering an educational system that respects and honors the cultural identities of Native students. Understanding Colonialism in Education: To comprehend the importance of decolonizing school leadership, it's crucial to recognize how colonial structures have shaped and continue influencing educational systems. Colonial education models often:

1. Prioritize Western knowledge and epistemologies

2. Marginalize Indigenous and non-Western ways of knowing

3. Perpetuate hierarchical power structures

4. Promote assimilation rather than cultural preservation

5. Neglect the diverse needs and experiences of students from various cultural backgrounds

The Importance of Decolonizing School Leadership Practices:

1. Promoting Equity and Social Justice: Decolonizing leadership practices helps address systemic inequities that have historically disadvantaged Indigenous and minority students. By challenging colonial power structures, schools can create more equitable learning environments that support all students' success.

2. Enhancing Cultural Responsiveness: Decolonial approaches encourage leaders to recognize, value, and integrate diverse cultural perspectives into school policies, curricula, and practices. This cultural responsiveness can improve student engagement, academic achievement, and well-being.

3. Fostering Inclusive Decision-Making: Decolonizing leadership involves shifting from top-down, hierarchical decision-making to more collaborative, inclusive processes that value diverse voices and experiences.

4. Preserving and Revitalizing Indigenous Knowledge: By challenging the dominance of Western knowledge systems, decolonial leadership creates space for the preservation and revitalization of Indigenous languages, cultures, and ways of knowing.

5. Addressing Historical Trauma: Decolonizing practices acknowledge and address the historical trauma caused by colonial education systems, helping to heal intergenerational wounds and build trust between schools and communities.

6. Preparing Students for a Diverse World: Decolonial education better prepares all students to navigate and contribute to an increasingly diverse and interconnected global society.

7. Enhancing Critical Thinking: By exposing students to multiple perspectives and ways of knowing, decolonial approaches foster critical thinking skills and a more nuanced understanding of complex issues.

Strategies for Decolonizing School Leadership Practices:

1. Self-Reflection and Unlearning: School leaders must self-reflect to recognize and challenge their biases and colonial mindsets. This process involves unlearning ingrained assumptions and being open to new perspectives.

2. Inclusive Decision-Making: Implement collaborative decision-making processes that include diverse voices, particularly those from historically marginalized communities. This might involve creating advisory boards or adopting consensus-based models.

3. Curriculum Transformation: Work with educators to decolonize curricula by • Including diverse perspectives and narratives

• Challenging Eurocentric historical accounts

• Integrating Indigenous knowledge and ways of knowing

• Promoting critical analysis of colonial impacts

4. Cultural Competency Training: Provide ongoing cultural competency training for all staff members, focusing on understanding diverse cultures, recognizing bias, and implementing culturally responsive practices.

5. Community Engagement: Foster authentic partnerships with local communities, particularly Indigenous and minority groups. Involve community members in school governance, curriculum development, and cultural initiatives.

6. Language Revitalization: Support Indigenous language programs and multilingual education initiatives to preserve and revitalize endangered languages.

7. Restorative Practices: Implement restorative justice approaches to discipline, removing punitive measures that disproportionately affect minority students.

8. Diverse Representation: Actively recruit and retain diverse staff and leadership, ensuring that school personnel reflect the communities they serve.

9 Culturally Responsive Pedagogy: Encourage and support teachers in adopting culturally responsive teaching methods that honor diverse learning styles and cultural backgrounds.

10. Decolonial Assessment Practices: Develop assessment methods that recognize diverse ways of demonstrating knowledge and skills, moving beyond standardized testing that often reflects colonial biases.

Challenges and Considerations:

1. Resistance to Change: Those comfortable with the status quo or fearful of losing power and privilege may resist decolonizing leadership practices.

2. Lack of Resources: Implementing decolonial approaches often requires additional resources, training, and time, which can be challenging in under-resourced school systems.

3. Policy Constraints: Existing educational policies and standards may limit how schools can implement decolonial practices.

4. Balancing Perspectives: School leaders must navigate the complex task of honoring diverse cultural perspectives while meeting academic standards and preparing students for broader societal participation.

5. Avoiding Tokenism: There's a risk of superficial implementation that needs to address deeper systemic issues, leading to tokenism rather than meaningful change.

Decolonizing school leadership practices is a complex but essential process for creating more equitable, inclusive, and culturally responsive educational environments. By challenging colonial structures and mindsets, school leaders can foster learning spaces that honor diverse perspectives, address historical injustices, and better prepare all students for success in a multicultural world.

This transformation requires ongoing commitment, self-reflection, and collaboration with diverse communities. While challenges exist, the potential benefits, including improved student outcomes, enhanced cultural preservation, and greater social justice, make decolonizing school leadership a critical imperative for 21st-century education. As educational leaders embark on this journey, they pave the way for a more inclusive, equitable, and culturally rich learning experience that empowers all students to thrive while honoring their diverse cultural heritages and ways of knowing.

Pillar # 3. Prioritization of Indigenous Knowledge

Central to the framework is the prioritization of Indigenous knowledge. Prioritizing Indigenous knowledge is not just a matter of cultural inclusion but a fundamental shift in educational philosophy that recognizes the value and validity of diverse ways of knowing. For non-Native school leaders, this prioritization requires a commitment to continuous learning, community engagement, and systemic change.

By centering Indigenous knowledge, these leaders can create educational environments that are more equitable, relevant, and empowering for Native students while also enriching the learning experience for all students. This approach honors Indigenous communities' cultural heritage and prepares all students for a more diverse and interconnected world. Non-Native school leaders must recognize the rich cultural heritage and wisdom embedded within Indigenous communities.

School leaders can provide students with a holistic and culturally relevant learning experience by incorporating Indigenous knowledge into the curriculum and educational practices. Prioritizing the Indigenous Knowledge pillar also emphasizes the importance of honoring and preserving traditional knowledge systems within the academic setting.

The Importance of Prioritizing Indigenous Knowledge:

1 Cultural Preservation and Revitalization: Prioritizing Indigenous knowledge in education plays a crucial role in preserving and revitalizing cultures historically marginalized or threatened by colonization. By integrating traditional knowledge into educational systems, schools can become cultural continuity and resurgence sites.

2. Enhanced Student Engagement and Achievement: When Indigenous students see their cultures, languages, and ways of knowing reflected in their education, they are more likely to engage deeply with the learning process. This cultural relevance can improve attendance, academic achievement, and graduation rates.

3. Holistic and Sustainable Worldviews: Indigenous knowledge systems often encompass holistic perspectives that emphasize the interconnectedness of all living things. These worldviews can contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of complex issues such as environmental sustainability, community health, and social justice.

4. Decolonization of Education: Prioritizing Indigenous knowledge is critical in decolonizing educational systems with historically privileged Western perspectives. This process helps to address historical injustices and creates a more equitable and inclusive learning environment for all students.

5. Cross-Cultural Understanding: Incorporating Indigenous knowledge into mainstream education can foster greater cross-cultural understanding and respect among non-

Indigenous students and educators contribute to a more harmonious and diverse society.

Critical Areas of Leadership for Prioritizing Indigenous Knowledge:

1. Curriculum Development: Educational leaders have a significant opportunity to prioritize Indigenous knowledge through curriculum design and implementation. This can involve:

Integrating Indigenous perspectives across all subject areas

Developing courses specifically focused on local Indigenous cultures and histories

Incorporating Indigenous languages into the curriculum

2. Pedagogical Approaches: Leaders can promote teaching methods that align with Indigenous ways of learning, such as:

• Experiential and land-based learning

• Storytelling and oral traditions

• Collaborative and community-based learning approaches

3. School Governance and Policy: Educational leaders can prioritize Indigenous knowledge by:

• Including Indigenous representation in school boards and decision-making bodies • Developing policies that support the integration of Indigenous knowledge and practices

• Creating partnerships with local Indigenous communities and organizations 4. Teacher Training and Professional Development: Leaders can ensure that educators are equipped to integrate Indigenous knowledge by:

• Providing ongoing cultural competency training

• Offering professional development focused on Indigenous pedagogies • Supporting the recruitment and retention of Indigenous educators

5. Community Engagement: Educational leaders can prioritize Indigenous knowledge by • Establishing elder-in-residence programs

• Creating community advisory boards

• Facilitating regular community consultations and collaborative projects 6. Resource Allocation: Leaders can demonstrate their commitment to Indigenous knowledge by:

• Allocating funds for Indigenous language programs

• Investing in culturally appropriate learning materials and resources

• Supporting Indigenous-led educational initiatives and research

Barriers to Prioritizing Indigenous Knowledge:

1. Systemic Racism and Colonialism: Deeply ingrained colonial structures and attitudes within educational systems can resist the integration of Indigenous knowledge and perspectives.

2. Lack of Understanding and Awareness: Many non-Indigenous educators and administrators may need to be more aware of the importance and validity of Indigenous knowledge systems.

3. Limited Resources: Schools often face budget constraints that can make implementing new programs challenging or acquiring necessary resources for Indigenous knowledge integration.

4. Standardized Testing and Curriculum Requirements: Rigid state or national curriculum standards and high-stakes testing can create pressure to focus on Western knowledge systems at the expense of Indigenous perspectives.

5. Shortage of Indigenous Educators: There is often a lack of Indigenous teachers and administrators, which can make it challenging to integrate Indigenous knowledge into schools authentically.

6. Cultural Appropriation Concerns: Fear of inappropriately using or misrepresenting Indigenous knowledge can sometimes lead to hesitation in incorporating it into educational settings.

7. Resistance to Change: Some stakeholders, including parents, teachers, or community members, may resist changes to traditional educational approaches.

Strategies for Overcoming Barriers:

1. Comprehensive Cultural Competency Training: Provide ongoing, in-depth training for all staff members to build understanding and appreciation of Indigenous knowledge systems.

2. Collaborative Partnerships: Develop strong, reciprocal partnerships with local Indigenous communities to ensure authentic representation and integration of knowledge.

3. Policy Reform: Advocate for local, state, and national educational policy changes to create more space for Indigenous knowledge in curriculum and assessment practices.

4. Resource Development: Invest in creating and acquiring culturally appropriate learning materials and resources that reflect Indigenous knowledge.

5. Indigenous Leadership: Actively recruit and support Indigenous educators and administrators and create pathways for Indigenous leadership within educational institutions.

6. Community Engagement: Foster ongoing dialogue and collaboration with Indigenous communities to ensure knowledge is shared and integrated respectfully and appropriately.

7. Flexible Implementation: Develop flexible approaches to integrating Indigenous knowledge that can be adapted to different contexts and constraints.

Prioritizing Indigenous knowledge in educational leadership is not just a matter of cultural inclusion but a fundamental shift in how we approach education, knowledge, and learning. By centering Indigenous perspectives, educational leaders can create more equitable, relevant, and holistic learning environments that benefit all students.

While barriers exist, they can be overcome through committed leadership, community collaboration, and a willingness to challenge and transform existing educational paradigms. As we move towards a more inclusive and diverse global society, prioritizing Indigenous knowledge in education becomes important and essential for creating a more just and sustainable future.

Pillar # 4. Culturally Affirming Practices

Culturally affirming practices are the second pillar of the leadership Framework for non-Native School Leaders. Understanding and implementing culturally affirming practices is crucial for non-Native school leaders working with Native American students and communities. In the realm of education, the implementation of culturally affirming practices holds immense significance, particularly for non-Native school leaders working in predominantly Native-enrolled schools. Culturally affirming practices go beyond mere recognition of cultural diversity; they involve actively validating and celebrating the rich heritage, knowledge, and traditions of Native Peoples.

Culturally Affirming Practices underscore the importance of creating a school environment that validates and uplifts the cultural identities of Native students. Non-Native school leaders must implement policies and practices that respect and reflect the diverse cultural backgrounds of the student body.

By fostering a sense of belonging and cultural pride, school leaders can nurture an inclusive and supportive learning environment where students feel valued for who they are. Much work has been done on culturally responsive pedagogy in today's educational landscape. This work has been instrumental in reshaping the conversations around educating Native students. The Leadership Framework for non-Native School Leaders recognizes this work, and this framework felt it essential to include culturally affirming practices as a pillar as they go beyond the tenets of culturally responsive practices.

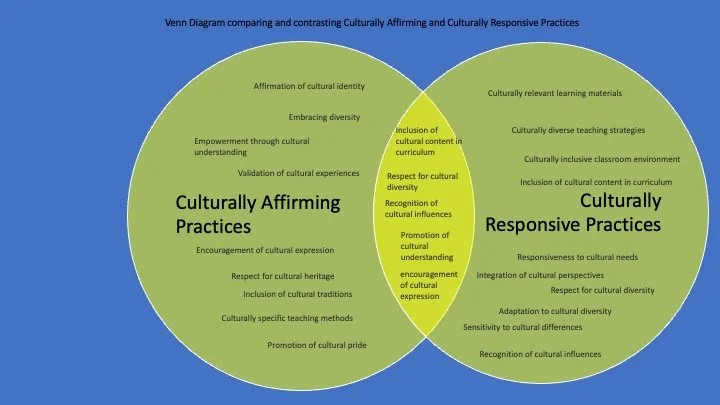

Culturally Affirming vs. Culturally Responsive Practices

Figure # 2

A Venn diagram comparing and contrasting culturally affirming and culturally responsive practices. Created by: Dr. Ralph M. Watkins. July 24th, 2009

While culturally responsive practices emphasize adapting teaching methods and curricula to meet the diverse needs of students from various cultural backgrounds, culturally affirming practices take this concept a step further. Culturally affirming practices acknowledge students' cultural identities and affirm, validate, and uplift those identities within the educational context. These practices go beyond surface-level inclusivity to create an environment where students feel a deep sense of belonging and pride in their cultural heritage.

Understanding Culturally Responsive vs. Culturally Affirming Practices

Culturally Responsive Practices in education involve adapting teaching methods and curricula to be more inclusive of diverse cultural backgrounds. These practices aim to make learning more relevant and effective for students from various cultural groups. Key aspects include: 1. Acknowledging cultural differences

2. Incorporating diverse perspectives into the curriculum

3. Adapting teaching styles to match students' cultural learning preferences 4. Building bridges between academic concepts and students' lived experiences

While culturally responsive practices are valuable, they often fail to embrace and elevate students' cultural identities fully. Culturally Affirming Practices Culturally affirming practices take a step beyond responsiveness, actively celebrating and integrating students' cultural identities into the education fabric. These practices:

1. Explicitly value and uplift students' cultural backgrounds

2. Integrate cultural knowledge and practices into core curriculum and school operations 3. Empower students to be proud ambassadors of their heritage

4. Actively combat cultural erasure and stereotypes

5. Involve the community in shaping educational practices and policies

For Native American students, culturally affirming practices go beyond mere acknowledgment to true celebration and integration of Native culture, knowledge, and traditions.

Recognizing and Affirming Native Culture, Knowledge, and Traditions. Culturally affirming practices for Native students involve several key elements:

1. A. Integration of Native Languages

a. Offering Native language classes

b. Incorporating Native languages into school announcements, signage, and events c. Supporting Native Language Immersion Programs

2. Honoring Traditional Knowledge

a. Inviting tribal elders and knowledge keepers as guest lecturers

b. Incorporating traditional ecological knowledge into science curricula

c. Recognizing traditional medicinal practices in health education

3. Celebrating Native History and Contemporary Achievements

a. Teaching accurate, comprehensive Native history

b. Highlighting contemporary Native leaders, artists, and innovators

c. Organizing school-wide celebrations of Native American Heritage Month 4. Respecting Native Traditions and Spirituality

a. Allowing excused absences for participation in tribal ceremonies

b. Creating spaces for smudging or other spiritual practices

c. Incorporating traditional storytelling into literature and social studies

5. Embracing Native Art and Culture

a. Displaying Native artwork throughout the school

b. Offering classes in traditional Native art forms

c. Incorporating Native music and dance into school performances

6 Recognizing Tribal Sovereignty

a. Teaching about tribal governance and sovereignty

b. Collaborating with tribal education departments

c. Respecting tribal jurisdiction in relevant matters

Examples of Positive Effects of Culturally Affirming Leadership Practices

1. Improved Academic Performance When school leaders implement culturally affirming practices, Native students often experience improved academic outcomes. For example, a study of Native American students in Alaska found that those who participated in a culturally based education program significantly improved their reading and math scores compared to their peers in standard programs.

2. Increased Attendance and Graduation Rates Schools that embrace culturally affirming practices often see higher attendance rates among Native students. The Navajo Nation, for instance, reported a 30% increase in high school graduation rates after implementing a comprehensive, culturally affirming education program.

3. Enhanced Cultural Pride and Identity Culturally affirming practices can boost students' cultural pride and identity. A survey of Native American high school students in a culturally affirming school environment showed that 85% reported feeling proud of their heritage, compared to only 45% in schools without such practices.

4. Stronger School-Community Relationships When school leaders actively affirm Native culture, it often leads to stronger relationships between the school and the Native community. For example, a school district in Montana that implemented culturally affirming practices saw a 50% increase in parent involvement and a 75% increase in community partnerships over three years.

5. Reduced Disciplinary Issues Schools that implement culturally affirming practices often see a reduction in disciplinary issues among Native students. A study in Washington state found that schools with vital culturally affirming programs had 40% fewer suspensions of Native American students compared to similar schools without such programs.

6. Improved Mental Health Outcomes Culturally affirming practices can positively impact students' mental health. Research has shown that Native American students in culturally affirming school environments report lower rates of depression and anxiety compared to those in standard school settings.

7. Increased Teacher Retention and Satisfaction When school leaders implement culturally affirming practices, job satisfaction among teachers, particularly Native American educators, often increases. A survey of Native American teachers in culturally affirming schools showed a 25% higher retention rate than those without such practices.

For non-Native school leaders, implementing these practices can lead to significant positive outcomes for Native students, including improved academic performance, increased cultural pride, stronger community relationships, and better mental health outcomes. By fully embracing and elevating Native culture within the educational setting, school leaders can create more inclusive, equitable, and effective learning environments for all students.

Pillar # 5. Collaboration

Meaningful collaboration between non-Native school leaders and Indigenous stakeholders is not just a matter of good intentions; it requires a fundamental shift in mindset, a commitment to cultural humility, and a willingness to share power authentically. By embracing the principles of respect, relationship-building, and shared decision-making, school leaders can overcome barriers and forge partnerships that truly serve the educational aspirations of Indigenous students and communities. This work is not easy, but it is essential for creating educational environments that value diversity, promote equity, and honor the unique contributions of Indigenous peoples. Through meaningful collaboration, non-Native school leaders and Indigenous stakeholders can work together to transform schools into spaces of cultural revitalization, academic excellence, and community empowerment.

By fostering collaborative relationships built on mutual respect and trust, school leaders can ensure that decisions are made collectively, with the community's input and perspectives at the forefront. Collaboration enables school leaders to leverage the collective wisdom and expertise of Indigenous communities to drive positive change in the educational landscape.

Principles of Meaningful Collaboration

Respect for Tribal Sovereignty

Meaningful collaboration recognizes and respects the inherent sovereignty of Indigenous nations. This means acknowledging the authority of tribal governments and working in partnership with them to make decisions that impact Native students and communities. This respect is foundational to building trust and ensuring that collaborations are equitable and respectful 1

Cultural Humility

Authentic collaboration requires non-Native school leaders to approach their work with cultural humility. This involves recognizing the limitations of one's cultural knowledge, being open to learning from Indigenous perspectives, and embracing the ongoing process of cultural competency development.

Valuing Indigenous Knowledge Systems

Meaningful collaboration values and incorporates Indigenous ways of knowing, learning, and teaching. This includes recognizing the importance of traditional knowledge, oral histories, and place-based learning in the educational process.

Relationship-Building

Building trusting, reciprocal relationships is at the heart of authentic collaboration. This requires time, consistency, and a genuine commitment to understanding and respecting Indigenous communities' unique histories, cultures, and priorities.

Shared Decision-Making

Meaningful collaboration involves shared decision-making processes that give Indigenous stakeholders equal voice and power. This means moving beyond token consultation to co-create educational policies, programs, and practices.

Holistic Approach

Authentic collaboration takes a holistic view of education, recognizing the interconnectedness of academic, cultural, social, and emotional well-being. This requires working together to address the factors that impact Native student success inside and outside the classroom.

Barriers to Authentic Collaboration

Historical Trauma

The legacy of colonization, forced assimilation, and educational oppression has created deep wounds and mistrust between Indigenous communities and academic institutions. This historical trauma can make building trusting relationships challenging and engaging in authentic collaboration.

Power Imbalances

Traditional Western educational models often perpetuate power imbalances that marginalize Indigenous voices and decision-making authority. These imbalances can create resistance to collaboration and undermine shared leadership principles.

Cultural Misunderstandings

Lack of cultural knowledge, sensitivity, and competency among non-Native school leaders can lead to misunderstandings, miscommunications, and unintentional offenses that damage collaborative relationships.

Systemic Inequities

Persistent disparities in funding, resources, and educational opportunities for Native students and schools can create barriers to effective collaboration. These inequities strain partnerships and limit the capacity for meaningful engagement.

Bureaucratic Constraints

Rigid bureaucratic structures, policies, and procedures within educational systems can hinder the flexibility and responsiveness needed for authentic collaboration with Indigenous communities.

Time and Distance

Geographic isolation and the time-intensive nature of building relationships across cultural boundaries can pose practical challenges to consistent, face-to-face collaboration.

Strategies for Overcoming Barriers and Fostering Meaningful Collaboration

1. Commit to Cultural Competency

• Provide ongoing cultural competency training for all school staff, including non-Native leaders.

• Encourage experiential learning through participation in community events and cultural activities.

• Seek guidance from cultural advisors and elders to inform collaborative processes •

2. Establish Trust Through Consistent Action

• Follow through on commitments and maintain open, honest communication. • Demonstrate respect for tribal sovereignty and community protocols in all interactions. • Prioritize relationship-building, even when it requires slowing down decision-making processes

3. Create Inclusive Governance Structures

• Develop collaborative leadership models that include Indigenous representation at all levels.

• Establish advisory councils or committees that give equal weight to Indigenous perspectives.

• Implement consensus-based decision-making processes that align with Indigenous values

4. Advocate for Equitable Resources

• Work with tribal education departments to identify and address resource disparities. • Collaborate on grant-writing and fundraising efforts to support Indigenous-led initiatives. • Use your platform to advocate for systemic changes that promote educational equity for Native students

5. Adapt Policies and Procedures

• Review and revise school policies to remove barriers to collaboration and cultural responsiveness.

• Develop memorandums of understanding (MOUs) with tribal governments to formalize partnerships.

• Create flexibility in schedules, curricula, and assessments to accommodate cultural priorities

6. Utilize Technology for Remote Collaboration

• Leverage video conferencing and online platforms to facilitate regular communication. • Use social media and community radio to share information and gather feedback. • Explore innovative ways to connect students and classrooms across geographic distances.

7. Center Indigenous Voices and Expertise

• Invite Indigenous leaders, elders, and knowledge-keepers into the school as teachers and mentors.

• Prioritize the hiring and retention of Indigenous educators and staff.

• Amplify Indigenous voices in curriculum development, program planning, and evaluation processes

8. Embrace a Holistic Approach

• Collaborate on initiatives that address the social, emotional, and cultural needs of Native students.

• Partner with community organizations to provide wrap-around services and support. • Integrate Indigenous languages, arts, and cultural practices into all aspects of the educational experience

Through meaningful collaboration, non-Native school leaders and Indigenous stakeholders can work together to transform schools into spaces of cultural revitalization, academic excellence, and community empowerment.

Conclusion

The Non-Native School Leader Leadership Framework provides a roadmap for non-Native school leaders to navigate the complexities of serving in predominantly Native-enrolled schools. By embracing the pillars of Native Educational Sovereignty, culturally affirming practices, prioritization of Indigenous knowledge, collaboration, and decolonization of leadership practices, school leaders can create an inclusive and culturally responsive educational environment. Through intentional and thoughtful leadership, non-Native school leaders can ensure that Native students excel academically and leave their schools with their language, culture, and cultural identities intact.